Why I Wrote Monticello

The Declaration is the best piece of Resistance writing even now, so elegant in style. That’s why John Adams deferred to Jefferson to write it. Alas, being a slaveholder, Jefferson is out of favor, even if his own political radicalism arguably set or helped set the fire to the Abolition movement that ended slavery. Lincoln, who kept moving to the left and ending slavery, did so because with each passing year he seemed more and more to be channeling Jefferson. Jefferson created Lincoln: one great writer helped shape another. And the Declaration – that most extreme of all calls to Resistance – set fire to the French in 1789, set fire to Garrison and others, and should, I wish, be setting fire to us today.

That’s why I am now about to put on a play about him.

How did I get hooked on him? Long ago – I must have been in sixth grade – my grandmother bought me a three- volume life of Jefferson by Claude G Bowers, FDR’s Ambassador to Republican Spain. Bowers was way out there on the left. My grandmother, an Ohio Republican, had no clue how radical on the left was the Jefferson in these books.

Bowers made out the Federalists, now so celebrated in hip-hop, as the most evil cabal and wrote about them in terms that only Lenin or Marx would use of capitalists; here was a minority determined to use a Constitution hostile to popular rule in order to subvert democracy and liberty and keep royalist one percent in charge. And it is no wonder that Lincoln the Whig started to become so utterly Jeffersonian, when the anti-slavery majority of the North kept losing out in the 1850s to a determined minority like the Federalists had been: a reactionary cabal that sought to stay in power by spreading slavery in Kansas and Nebraska and over the continent.

It is important to remember that Jefferson did not just inspire the “First Resistance” to the British, but also an entire “Second Resistance” to Federalists who displaced the royalists as the enemies of the left. Think of the danger he was in from the Alien and Sedition Act, which made political speech criminal (far worse than Trump’s travel ban today). It is Jefferson who – out of favor as a slaveholder, as he should be – is also out of favor as an opponent of fascism, as Bowers saw him.

In that Second Resistance, Jefferson wanted not just to beat the Federalist Party but destroy it. Utterly. And he did.

The Jefferson who conspired against President Washington while serving in his cabinet did not just support the French Revolution. He applauded the execution of the King and the Queen.

It’s Jefferson not only of the First but Second Resistance, the Jefferson calling all of us to resist, who made me want to write a play.

After all, when I was 12 and 13, during the Cold War, when I should have been having nightmares about the Russians, I used to have nightmares about Hamilton and his royalist friends and how they might come back. Well, now I am having nightmares again, and I think of Bowers’ Jefferson as the best talisman in the time of Trump: better than even Lincoln.

That’s the puzzle: who is this Jefferson, saintlier in those books I read than even the sainted Orwell?

That puzzling has now led me to an act of financial catastrophe, to let Jefferson get up on the stage and have his say.

This is not an attack on Hamilton, a great and wonderful theatrical event. Indeed, when I wrote this play – or had the idea of it – Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton had not even appeared. But I was trying to figure out what Jefferson would have to say to us today.

One way of putting the question of our time: was Jefferson wrong to believe that we are capable of self-government? And why is it that almost no one sees the Declaration, our founding document, as a call to resist?

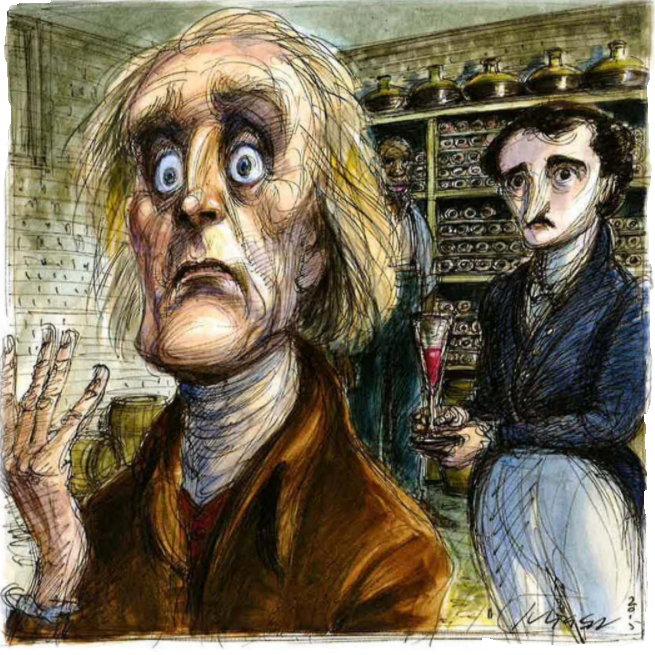

First of all he needed to deliver the message on a dark and stormy night. Also, in delivering it, he needed the right person up there to listen. I guess I could have picked James Madison, but Madison is kind of a yawn. On the other hand it is going too far to have him chatting up there with Orwell. Edgar Allan Poe, though, seems just about right.

Over and over, friends who have heard that I placed Jefferson and Poe together through one long and tormented night say to me: “But of course they weren’t contemporaries.”

Oh they very much were contemporaries. Do you think I’d make that up?

Jefferson, the founder of the University of Virginia, used to invite students to dine with him at Monticello. In 1826, the last year of his life, Edgar Allan Poe enrolled as a student, yes, just yards away from Monticello. So just before Jefferson’s death – on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration, July 4, 1826 – Poe might have gone up to dine with Jefferson.

Well, it could have happened, and he did show up for Jefferson’s funeral just after July 4 in that year.

So this play is a riff on a meeting that might have occurred.

But as I got into writing it, and letting Jefferson on the eve of July 4, 1826, explain to Poe what the Declaration really meant, a funny thing happened:

The subject of slavery kept popping up. Sally Hemings kept coming into the room and so did others, “the Monticello staff.” So the play also has to deal with what may be the single strangest thing about the United States of America, then or now: that the whole thing could come out of the imagination of an egalitarian, practically an anarchist, who would not even free his slaves.

It was not enough to let Jefferson have his say: those who despise him as a slave master also had to have their say. Indeed, in Act II, I tried to conjure the worthiest possible opponent, Toussaint L’Ouverture, who most haunted the imagination of Jefferson and the slave-owning South. If he has the interesting take on Jefferson, then Jefferson of this play also has an interesting take on him.

What does Poe have anything to do with this?

The very young Poe, a writer in formation, is the perfect person to see, as I hope the audience will, that Monticello is both the country’s glorious temple of reason but its nascent House of Usher. Poe is up there to help us hear the screams.

But then, we’re all living in the House of Usher now, aren’t we? In the Trump era, there are plenty of screams coming up from the basement.

While Jefferson may have ended up as a prisoner of Monticello, unable even to free himself, he has a far deeper vision of liberation than anything in 1984 or in any of its current literary competitors. I don’t ask that people see the play – well, I do sort of – but I would love to see them read The Book, the Declaration itself.

For indeed, even now in the Trump era, we are still the once and future People of the Book, and the document signed on July 4, 1776, is the greatest of all literary calls to resist.

Leave a Reply